BY RACHEL A. ROEMHILDT / Dec 25, 1998

Insight on the News

Hollywood isn't producing films families want, say critics of Tinseltown who are taking the matter into their own hands -- by editing sex and profanity from videos of well-known movies.

Don and Carol Biesinger, owners of Sunrise Video in American Fork, Utah, have been splicing out nudity and sex from copies of the Paramount film Titanic. For $5 apiece, the Biesingers happily edit tapes sent to them by families who want wholesome entertainment.

"We have actually had to hire a shipping clerk just to handle all the orders" says Carol. "The phone never stops ringing."

While Paramount has cried foul, the idea could catch on nationally as other video-store owners figure out ways to turn PG films into G-rated flicks. Sunrise Video will edit whatever the customer finds objectionable, except for profanity, which requires more sophisticated technology.

"Seven out of 10 individuals say they have a problem finding appropriate family entertainment," says Don Judd, vice president of production and acquisitions for Feature Films for Families, a Utah-based production and distribution company. While "dating demographics" -- moviegoers age 14 to 29 -- continues to drive the box office, the wholesome-entertainment trend is growing. Organizations such as the Dove Foundation, a nonprofit organization based in Grand Rapids, Mich., are encouraging the movie industry to promote quality films deemed appropriate for family viewing.

"We have long been advocates of Hollywood editing their own films and producing them" says Dick Rolfe, president of Dove Foundation. The organization provides a list of movies it deems appropriate for family viewing without editing, listing the titles in its newsletter and on its Internet site.

Meanwhile, Principle Solutions offers a device called "TV Guardian: the Foul Language Filter," which mutes profanity in favor of closed caption substitutions of the offending phrases. The Rogers, Ark., company has sold more than 3,000 TV Guardians since March, according to the chief executive officer, Mike Seals.

Film companies do produce edited versions of their films for airline use. But Paramount has threatened legal action against the unauthorized editing by the Biesingers. "There is a great irony there because [movie producers] will allow a film to be edited for airline use or for television, but not for home use" says Judd.

The Biesingers say they will comply with Paramount if they are found in violation of the law. For such editing to be illegal, they claim, they would have to make a copy of the video, then edit and resell it; editing personal copies of the film is another matter, "the electronic equivalent of buying a book or magazine and tearing out several pages" says Charles Henry Grant, a Washington lawyer who specializes in entertainment and copyright law.

Studios cite "artistic integrity" as another reason to oppose editing, although others scoff at that notion. "It is not an issue of squelching the creative nature of the film; it is a matter of money" says Rolfe. "For $30 million, Paramount will let Titanic be edited" NBC bought the television fights to the film, which will be edited before it airs.

Friday, December 25, 1998

Thursday, September 10, 1998

FOR $5 A FAMILY VIDEO STORE WILL CUT 2 'TITANIC' SCENES

BY MATT RICHTEL / Sep 10, 1998

BY MATT RICHTEL / Sep 10, 1998The New York Times

James Cameron won an Oscar for directing ''Titanic.'' Now Carol Biesinger, the owner of a video rental store in Utah, is winning business for making some creative cuts to the biggest-selling movie of all time.

For $5, Sunrise Family Video in American Fork, Utah, which does not rent R-rated movies, will cut two steamy scenes from home video copies of ''Titanic.'' Ms. Biesinger said she had got the idea after customers complained they would not be able to share it with their children.

The scenes Ms. Biesinger trims in her back office include one in which Kate Winslet, who plays the heroine, appears topless and one in which she and her co-star, Leonardo DiCaprio, steam up the windows of an automobile. For an additional $3, Ms. Biesinger will cut other scenes at the customer's request.

''We had customer after customer come in and talk about the movie,'' she said. ''They said they couldn't sit on the couch and watch it with the family without being embarrassed.''

The procedure to cut the film and takes only 10 minutes, she said. But, thanks to the more than 1,000 orders Sunrise video has received for the surgical procedure, the wait is five weeks.

The wait is not the only sticking point. Ms. Biesinger said she had received a call from Paramount Pictures asking her to cease her unilateral cutting and pasting.

She said she had told the movie house that she would do so ''when they proved it is illegal.'' Then, she said, she will quit.

''I'm not out to break the law,'' she said. ''We're just trying to meet a demand.''

Saturday, August 1, 1998

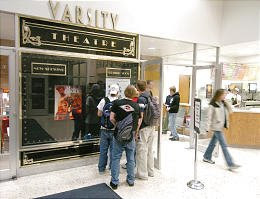

VARSITY THEATER STOPS EDITING

BY MARY LYNN BAHR / Aug 1, 1998

BY MARY LYNN BAHR / Aug 1, 1998BYU Magazine

When the Wilkinson Center opened in 1964, some of the first films shown in the Varsity Theatre were Don't Go Near the Water (1957) and The Wackiest Ship In the Army (1961), starring Jack Lemmon. A recent policy change has brought films from that era back to the Varsity: During September and October, BYU students enjoyed such films as The African Queen (1951), Rebel Without a Cause (1955), and Alfred Hitchcock's The Birds (1963).

Classic films are back because the Varsity is no longer editing movies, and few current films meet BYU's standards.

A policy change had been considered for some time, but the process accelerated in January, when Sony Pictures requested that BYU stop editing its films. The university immediately complied, pulling all Sony films from the winter semester schedule.

BYU receives movies through an intermediary distributor who had always known that films were edited before students saw them. "They knew that we were doing it and raised no objection," says Jerry L. Bishop, director of the Wilkinson Student Center. But Sony's request prompted administrators to contact other movie companies directly, seeking formal approval for contin-ued editing.

"Discussions with suppliers of films and film companies made it clear that BYU would not be able to secure formal approval to continue editing films," says Carri P. Jenkins, director of media communications. When formal approval could not be obtained, the university announced it would stop editing films beginning Aug. 4.

According to the new guidelines for movie selection, the Varsity Theatre will not show "movies containing nudity and/or sexual scenes (including lewd innuendos)" or "movies containing excessive (numerous, long running, specific, or extremely graphic) scenes of violence." The Varsity Theatre Film Review Committee may "exercise discretion and good judgment" in approving movies that contain profanity. Respectful references to deity and infrequent uses of "hell" and "damn" are permissible, but "other swearing, vulgarity, or profanity are not acceptable." No editing will be permitted.

The new policy also applies to BYU-Hawaii and Ricks College. "When BYU adopted the policy that we would not edit, that became a policy for all three schools," says Jenkins.

Responses to the policy change vary. Many students had appreciated the chance to view edited, big-name films. "The Varsity Theatre was a good place to go to see movies that we normally wouldn't be able to see, and for that reason it was a very attractive proposition to a lot of people," says J. Grant Robinson, a sophomore from Alpine, Utah, planning to major in theatre.

Some students expressed relief about the end of the editing policy. Tasi Young, a sophomore pre-med student from Salt Lake City, explains, "Even though I liked to see the edited movies, it always sat weird with me that someone else had to watch them to edit them."

Since editing is no longer permitted, the theater must find appropriate films in other ways. Classic films are the best option, Bishop says, though appropriate newer films will also be shown.

Dean W. Duncan, instructor of theatre and media arts, believes there is plenty of precedent for a successful repertory film program. The Department of Theatre and Media Arts sponsors a classic cinema course, and its public showings of classic films have drawn sizeable audiences. Duncan and other faculty from theatre and media arts support the university's decision to discontinue editing. A well-designed offering of older films could make the Varsity Theatre an effective educational vehicle, helping students "become more intelligent, empowered viewers," Duncan says. "I hope that we can move from this kind of escapist, passive, popcorn-chomping mode of viewing to a more active, citizenly, Christian form."

Though it caters to BYU students, the Varsity Theatre receives no BYU funds. R-rated films have always attracted the largest audiences, and without them the theater may struggle financially. Bishop explains, "One of our niches before was the fact that we were offering movies that were edited, and that was something they couldn't get in the community." Bishop is uncertain about how the student audience will receive older films: "It will be a matter of promoting, marketing, inviting people to come and try some of the old movies."

The new policy has already prompted some changes in marketing. As a first step, the Varsity cut ticket prices from $1.50 to $1. Also, though the Varsity has typically shown one movie per week, two movies are scheduled for each week of fall semester. Other marketing plans include two-for-one nights, theme weeks, and weeks highlighting a particular star, such as James Dean or Jimmy Stewart. The star approach seemed to work during the first weeks of fall semester, when the Varsity showed Audrey Hepburn films. According to Bishop, sales for Breakfast at Tiffany's matched average ticket sales from last year, and students packed the theater for Wait until Dark.

Ticket sales have fluctuated since then, but administrators remain positive. Jenkins is optimistic about the change: "We're hoping there's room for a different theater experience."

Labels:

BYU,

Mormon Culture,

Rated R,

Varsity Theater

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)